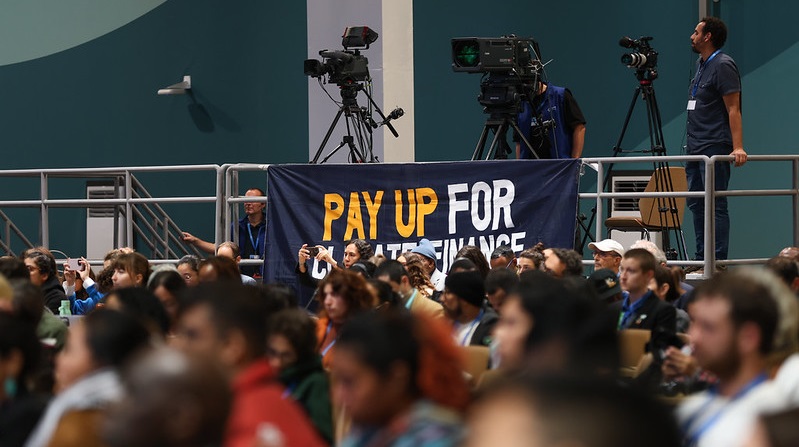

Campaigners have called on developing countries to walk away from finance talks rather than accept a bad deal This article will be updated throughout the day and an edited version will be sent out each evening as a newsletter – you can sign up here.

Campaigners: No deal better than a bad deal

As negotiations ground on to find agreement on the key new climate finance goal (NCQG) expected from COP29, climate justice campaigners called on governments to walk away from the summit rather than accept a weak outcome on behalf of workers, women and vulnerable communities around the world.

They insisted that no deal in Azerbaijan would be preferable to a “bad deal”.

Mohamed Adow, founder of Kenya-based think-tank Power Shift Africa said securing a strong deal for $1.3 trillion in international public finance as developing countries are demanding is central to success. “There can’t be a COP outcome if the rich world don’t step up and put forward an ambitious climate finance goal that meets the needs of the developing countries – period,” he said.

Developed and developing nations remain far apart on the amount of the new goal, as well as who should contribute towards it, as pressure grows on wealthier emerging economies – including China and the Gulf nations – to pay up too. Those countries don’t want to be put on a par with industrialised countries that are historically more responsible for the emissions fuelling global warming.

A draft text on the NCQG released on Thursday contained no specific figures on what developed countries are prepared to put on the table through to 2035, provoking a furious reaction from most developing-country groups who called on them to show their hand.

A new text is due to be released on Friday afternoon and is expected to contain some indication of the size of the goal.

Lidy Nacpil of the Asian Peoples’ Movement on Debt and Development, called on developing country governments to “be strong and united in the face of the Global North” and push them to recognise “what they owe us” for the rising damage done by climate change.

“We are really appealing and challenging our governments in the South to hold their ground and stand up for our rights,” she told journalists.

Adow said he feared that even though developing countries are “hugely disappointed” by the lack of progress in Baku “they are diplomats and so they would rather work behind the scenes and want to salvage a good outcome”.

He criticised the wealthy nations and the Azerbaijan COP presidency for not negotiating openly and “engaging eye to eye” with poorer countries.

Joseph Sikulu, Pacific regional director for 350.org, slammed the use of “stalling tactics” in Baku – which he said had happened in Dubai last year – and the lack of space to negotiate. That had left the process devoid of “values” such as including vulnerable and Indigenous peoples.

“We hope that over the next year we see more leadership from Indigenous peoples bringing these values into the negotiations and hope that they ground that in these presidencies,” he said, referring to the COP30 in Brazil next year.

Women’s rights and LGBTQ+ activists have also complained that the Azeri COP presidency has given a low priority to talks on the renewal of a key programme on gender and climate action, which have struggled amid pushback from socially conservative governments.

Liane Schalatek, speaking for the “women and gender constituency” of NGOs at COP29, said space for civil society had been restricted at the COP in Azerbaijan – which has a poor record on human rights and civil liberties – and the whole process had suffered from a lack of transparency.

“Also [governments] don’t know what is going on,” she told reporters in Baku, saying it was more important than ever to respect “the democratic ground rules that are the foundation basically of the climate regime”.

No finance deal better than bad deal, campaigners say